The Story Of Bear Rock

By: Bud Journey

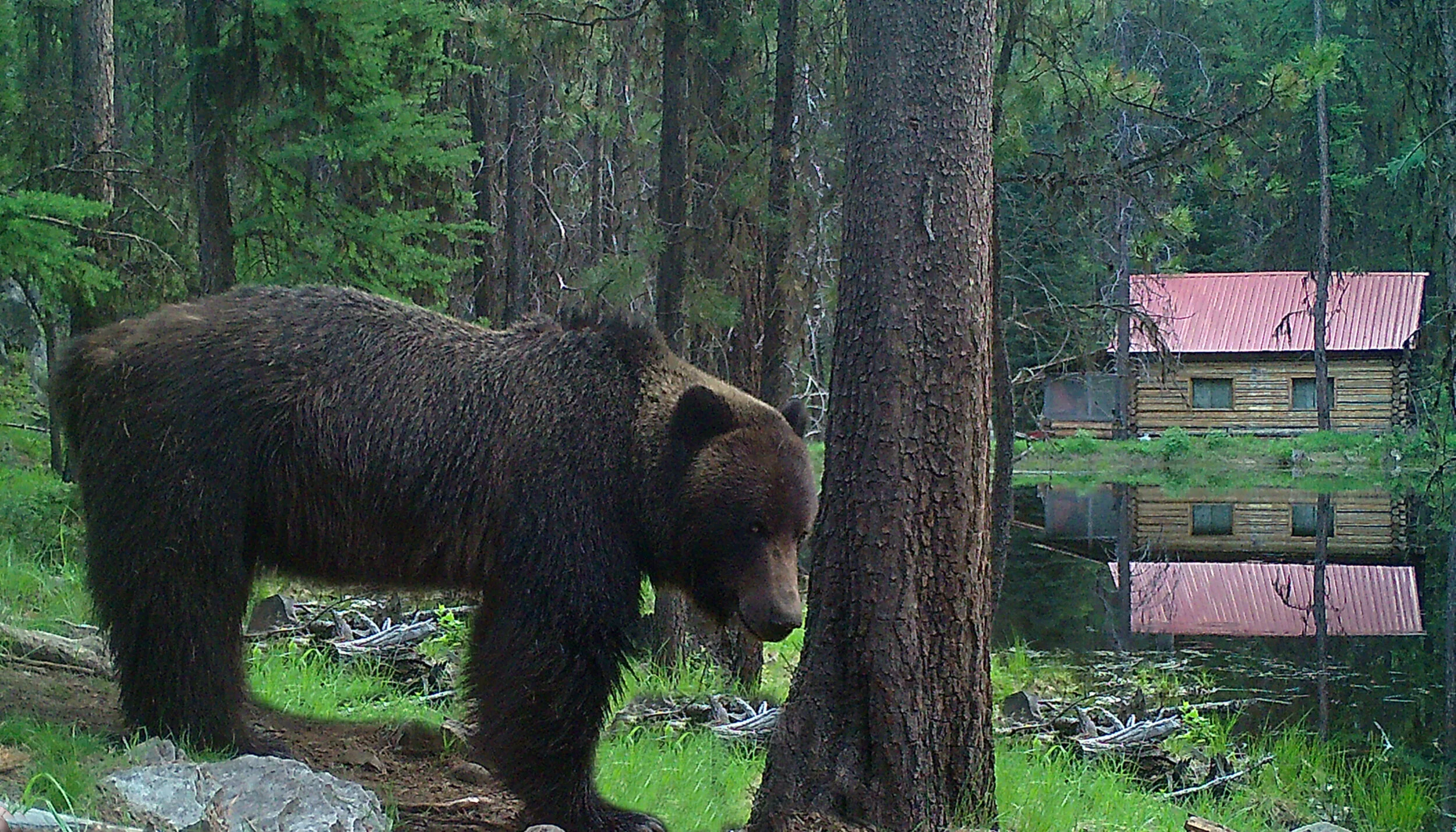

The author had a close encounter with a grizzly, lived to tell the tale and take a photo. Photo by: Bud Journey

One fine September day a few years back, I was fishing along a small stream in northwestern Montana’s Yaak River drainage. It was sunny, warm, and the fishing was good. I had already worked my way about a mile upstream from where I had parked the truck, and I continued northward, almost on automatic pilot, casting a gray hackle peacock wet fly from small pool to small pool as I moved. My plan was to go all the way to the Canadian border, about three to four miles upstream, then stroll leisurely back to the pickup, making the most of a perfect autumn day.

I was sublimely happy, contented, and in no hurry, enjoying the good weather and great fishing. Native cutthroats were cooperating nicely, eagerly taking my homemade fly just about everywhere I presented it, the perfect scenario for my favorite mode of fishing: catch-and-release. They ranged in size from about six inches to about a foot in length. It was the type of moment that I seemed to frequently experience in the Yaak.

The author in his element fishing in the Yaak. Photo by: Krisine Daggett

I was perhaps half way along my planned route to Canada, standing on a gravel bar between two branches of the stream. I was working my fly into a small pool at the upstream end of the gravel bar. On about the third cast, my sublime world was shattered by a loud hiss and the sound of brush crashing behind me. I turned around just as a grizzly bear came busting out of the streamside vegetation and splashing toward me, across the shallow branch of the creek. He stopped on the opposite end of my gravel bar, about 20 feet away, quartering toward me. The bear laid its ears back and cocked its head in my direction, its tiny eyes fixed on me: intense and unblinking. I held out my three-ounce flyrod with my left hand to ward off the bear, while I reached down and scooped up the biggest rock in the near vicinity with my right hand. I stood up as tall as I could muster out of my 5' 8" frame and slowly began backing away from the angry omnivore.

Avoiding direct eye-contact with the bear, I kept my vision oriented downstream, slightly askance of the bear's location, keeping track of it with my peripheral vision. As I backed away, I held the rock so the bear could see it, but not in a threatening manner. I talked emploringly but insistently to the bear: "Whoa, Bear. That's OK, Bear. Just stay where you are. Stay right there. I'm leaving, stay Bear, stay Bear. I'm leaving. Stay Bear."

The tip of my flyrod caught up in some limbs of an overhanging tree as I backed away. Meticulously, I worked the line loose, while negotiating my way over loose, underwater rocks, looking downstream, while keeping track of the bear out of the corner of my eye, and repeating the respectful and soothing (I hoped) litany: "Whoa, Bear. It's OK, Bear. Nice, Bear. Stay, Bear. Stay Bear. Please … stay, Bear."

After freeing the rod tip, I continued backing my way up the bank, through the streamside vegetation, snagging the line on what seemed like every bit of vegetation within the nine-foot reach of the now annoyingly long flyrod.

"Drop the damned fishing pole," I said, only to myself. “Forget the fishing pole; leave it. Let the bear chew it up, if necessary. Just drop it, and get the hell out of here.”

Just then, the grizzly moved aggressively back out of the brush, across the water, and onto the gravel bar. He stopped there, but his compelling gaze grabbed me and wouldn't let go. He stood, completely in control of the situation and daring me to do anything threatening. I assumed what I sincerely hoped to be my best neutral stance, eyes averted, and completely conceding dominance to the silvertip challenging me from 30 feet away.

The bear continued patrolling the gravel bar but made no more threatening moves toward me; still, he never let go with his eyes. I chanced a sideways step along the trail. The bear didn't deign to acknowledge the move, so I took another step. The bear stayed. I continued easing, crab-style, down the trail, rock in one hand and fishing pole in the other, keeping one eye on the bear and the other on the trail. Finally, the line of sight between us was broken by vegetation; I picked up the pace. Gripping the fly rod in one hand and cradling the hefty rock in the other, I moved purposefully away, fully expecting the griz to bolt across the water at any instant, and charge up the trail toward me.

He didn't.

I chanced another cautious move up the trail. With every 50 feet or so, I quickened my pace until I was maintaining almost a jog. About every third step, I glanced back over my shoulder, but the bear never appeared on the trail as I feared it might. During the ensuing 2-mile forced march, my body compelled me to take one brief stop at the top of a long uphill stretch. Then, I quickly resumed a brisk pace until I was all the way back to the truck, the rock still firmly gripped in my throwing hand. In a respectful gesture, I brought the rock back to the cabin and put it in a place of honor on the kitchen table. It didn’t look like the ultimate bear equalizer, but it was all I had, and somehow (maybe) it allowed me to separate from the bear. At the least, I could have perhaps given the bear a bit of a headache with it. At most … well, at most, I could have perhaps given the bear a bit of a headache – not much more. Still, the rock maintains a permanent place of respect on the kitchen table. It seemed like a good friend at one particularly anxious moment in my life.

Grizzlies are abundant in the Yaak river valley. Evidence of their presence can be found everywhere. Photo by: Bud Journey.

The grizzly was gray, brown, and silver in color: very shiny and quite beautiful, actually. It had no collars or ear tags to ugly it up. But it was a profoundly scary creature. A fight between a grizzly and an unarmed human is roughly comparable to a fight between a housecat and a canary. Even with a sharp flyrod and a hefty rock, the fight wouldn't last long. When I think about it, I also thank the grizzly for letting me off the hook. My impression of the bear was that it was a young adult -- likely protecting a food source. I saw no cubs -- luckily. Cubs would have probably been a death sentence for me. Still, I'm glad that I share the land with grizzly bears. They help make the Yaak almost unique, and very special.

Alfred E. "Bud" Journey was a full-time outdoors photojournalist during the 1970s, 80s, and 90s, including an 8-year stint as the Montana Editor for OUTDOOR LIFE in the 1980s. He has won numerous writing and photography awards in both the Northwest Outdoor Writers Association and the Outdoor Writers Association of America.